I wish that I could just buy the rubber-dome “scissor” key switches that my 2015 Macbook Pro has. I love these keys; I love the way they feel.

Unfortunately when you’re building your own keyboard, you have to use “mechanical” switches, and you have to be very snooty about them.

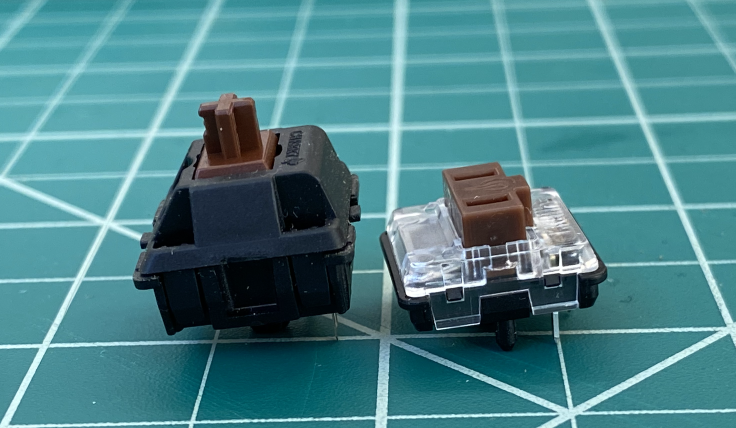

I decided to try “Kailh Low Profile Choc” switches, which stick up less than a traditional switch, and tend to come with flat, laptopesque keycaps.

I had never used Choc switches before, so I ordered a “switch tester” kit so I could decide which one I liked best.

There are, broadly, three types of Choc switches: tactile, linear, and clicky. There are two different clicky switches, and like five different linears, which vary only by the weight of their springs. There is only one “tactile” switch: the Choc brown.

I really liked the “feel” of the clicky switches, but I hated the way they sounded. The linears were silent, but I hated how they felt. So the browns won by default. They feel fine, and they’re just as quiet as the linear switches.

This was the result I was expecting going into this, but it was nice to try out all the options.

I did not know, at the time, that Choc browns have a hidden secret.

They rattle.

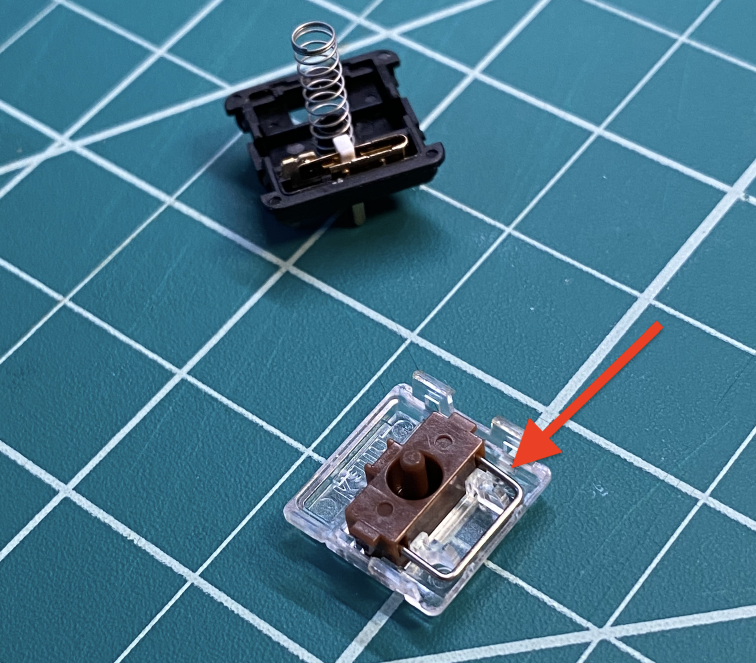

Inside every Choc brown switch is a little piece of metal shaped like a staple. That piece is just hanging out loose inside the switch, and at the slightest bump it will move around.

An entire keyboard full of them could make a pretty serviceable maraca. Since the whole point of a wireless split keyboard is that I can move it around freely, I really did not want to have any rattling parts in my keyboard.

So.

The internet consensus seems to be: take ‘em out.

Supposedly they act as stabilizers, so that if you press down on the edge a key, the key will remain relatively upright, instead of leaning to one side.

But the moving part of the key is held in a little plastic shaft, and it’s a pretty tight fit. There’s not really much room for it to lean, and even if it did, it’s not really clear to me that the metal stabilizer would do anything to correct it. The channels that the two prongs ride in just aren’t a tight enough fit.

I researched this a bit and found the general advice was that you can remove them without really affecting the switch in any way: most of the other Choc switches don’t have them in the first place, and those work fine.

But in order to remove them, you have to open up every switch.

I did not learn about this maraca effect until I had a case of fifty switches sitting in front of me.

I really didn’t want to open fifty switches up and remove a little metal staple from them.

I considered bailing on the switches, but I had already ordered keycaps as well, and Choc keycaps are not compatible with non-Choc switches. And the browns were the only Choc switches I liked.

So.

Fine.

I decided that, since I had to dissassemble every switch anyway, I should try to have some fun while I was in there.

In too deep

I had, at this point, learned of many subcultures in the mechanical keyboard world.

There are the ergonomic people. People like me who, after years of abusing their bodies with computers, developed some kind of repetitive stress injury and had to modify their tools in order to keep working at the unsustainable pace they’ve grown accustomed to. This is the only morally correct reason to build a keyboard, so we get to feel superior to all the other chumps who “have a hobby” that “brings them joy.” Pssh. Get some RSI already.

There are the minimalists. Perhaps this started as an ergonomic subgroup, but it’s evolved into something else: the minimalists are interested in combining keys and mod-tapping and layer one-shots and any sort of firmware customization that lets them get by with as few keys as possible. I do not know why.

There are the artistes. They buy fancy keycaps with color-coordinated cases, and they build keyboards with LEDs in them. Not even, like, to illuminate the keys. I’ve seen keyboards with LEDs on the bottom. Just to cast an annoying glare in your eyes? I don’t know. This subgroup seems to have the most disposable income.

And then there are the audiophiles. They don’t necessarily care how a keyboard looks, but they care deeply about how it sounds and feels. They will even go to great lengths to customize switches, replacing springs, lubricating the internal mechanisms, adding thin strips of tape as shims to shore up factory tolerances. They have opinions about case acoustics and material composition. They are, to an outsider, absolute nuts.

But I love the audiophiles. I love the crazy lengths they’ll go to to customize their incredibly expensive switches. And I wondered: what if they’re onto something? What if it really does make a difference? What if I’m missing out?

So I decided to try lubricating a switch.

Audiophiles talk about what a huge difference it makes, and I was curious if I could even hear it. And since I had to open up every switch anyway, to remove the stupid staple, it wasn’t much more work to rub some lubricant on it while I was in there.

So I bought a tube of lube, and I tried a test switch.

And I will reluctantly admit: I could hear the difference. And I did weakly prefer the sound of the lubricated switch.

One of the switches in that video is lubricated. One of them is not. Can you tell the difference?

I recorded that with my phone’s microphone, which is not necessarily the best for distinguishing subtle auditory differences. And I would say that, listening to the recording and the real thing side by side, the sound difference is slightly more noticeable in person.

Not enough that I would be willing do this if I didn’t already have to open up the switches anyway, but enough that I decided to go ahead and lubricate the rest of them.

I doubt I would actually notice if I were trying to type something and not actively trying to hear the difference, but whatever.

As you can tell I am insecure about this decision because even now it seems like a ridiculous thing to do. Why am I getting defensive? Because I’m worried that this is the first step on a slippery slope to becoming one of the audiophiles? Maybe. Maybe.

Lubricating 50 switches

The whole process took two hours and fifteen minutes. Two hours and fifteen minutes of opening switches, dissassembling them, lubricating the components, and finally reassembling them. I timed it.

I didn’t actually throw out the staplizers. I found that by bending them slightly, they would hold in tension against the switch’s pistony thing, and they wouldn’t rattle around anymore. But they’d still provide whatever nominal stabilization they were designed to provide. It only took a few seconds longer to bend and reinstall the stabilizers, so this seemed like a better approach than throwing them out. But I dunno. I didn’t do a test or anything.

One good reason to lubricate the switches is to reduce the likelihood of spring ping. This is a very annoying phenomenon that I have encountered before: the keyboard that I used before I built my Kyria has a few keys that occasionally ring out with this annoying sort of “ping” sound if I release them too quickly.

It bothers me, but not, like, a lot, and apparently adding lubricant to the springs makes it less likely. Because I guess it has a dampening effect or something. No idea if that’s true, but it meant I had to lubricate the springs.

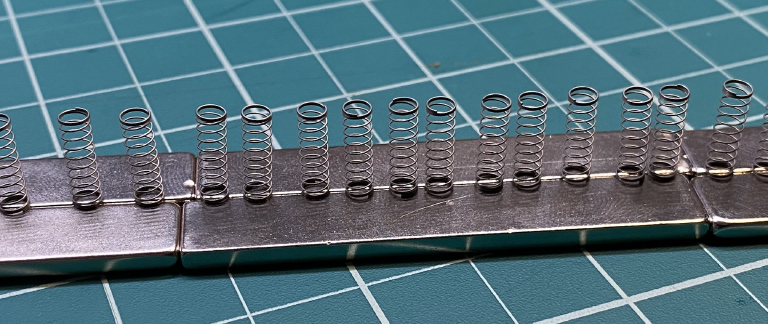

Lubricating springs is pretty fiddly, but I came up with what I think was a very good solution:

I used some bar magnets to hold the springs in place, so I could lubricate them all at once.

At first I tried with just one line of bar magnets, but the springs are attracted to the corners of the magnet, not the center, and it doesn’t take much force to knock them over so they adhere to the thin side. But by putting two bar magnets side-by-side, they stay perfectly aligned along the seam between them.

This worked great, and if you ever find yourself lubricating a lot of springs, I would recommend investing in $10 worth of bar magnets to make the job a lot easier. I happened to have these lying around, and I think it would have taken a lot longer without them.

After I reassembled each switch, I had my quality inspectors check them for any flaws.

Fortunately, they all passed.